Can a State Machine be a String?

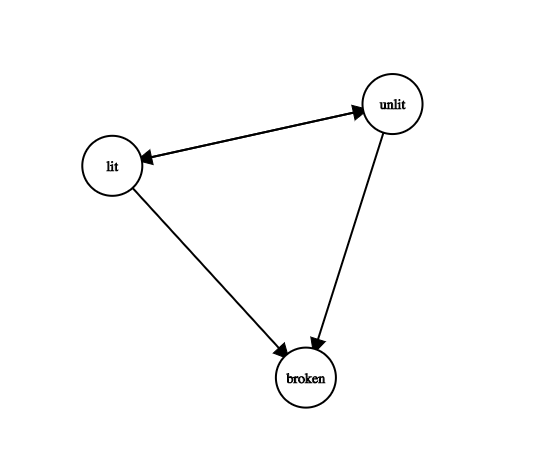

Near the end of last year, I was doing prep work for my first workshop on state machines. In my research, I came across this simple, but effective graph editor: https://csacademy.com/app/graph_editor/.

I was impressed with how simple it was to represent a graph with just a few lines of text. On the left side of the web page, under “Graph Data”, is a simple text input. You generate the graph by writing nodes next to each other. The light bulb example I used in the previous post is written like this:

lit unlit

unlit lit

lit broken

unlit brokenWhich generates this graph image:

I was blown away. A graph can be represented simply as a string if you followed a few rules. This got me thinking, “Can I do the same for a state machine?” Turns out you can.

In order to represent a state machine as a string, we only need to make a couple adjustments.

- We need to be able to derive an

idfrom our string - We need to be able to indicate the

initialstate - We need to be able to indicate what

eventswill trigger transitions

Accomplishing the first two criteria was pretty simple: dedicate the first two lines of our string to id and initial respectively. With our light bulb example, it would look like this:

lightBulb

unlitAdding the events required having a way to define an edge as an event type. I chose to accomplish the same way a weighted graph is represented as a string.

lit unlit TOGGLE

unlit lit TOGGLE

lit broken BREAK

unlit broken BREAKNow, we need a function that will parse this text into a valid state machine. Let’s setup the skeleton of that function.

function statechart(string) {

return {} // We'll eventually return a valid statechart here.

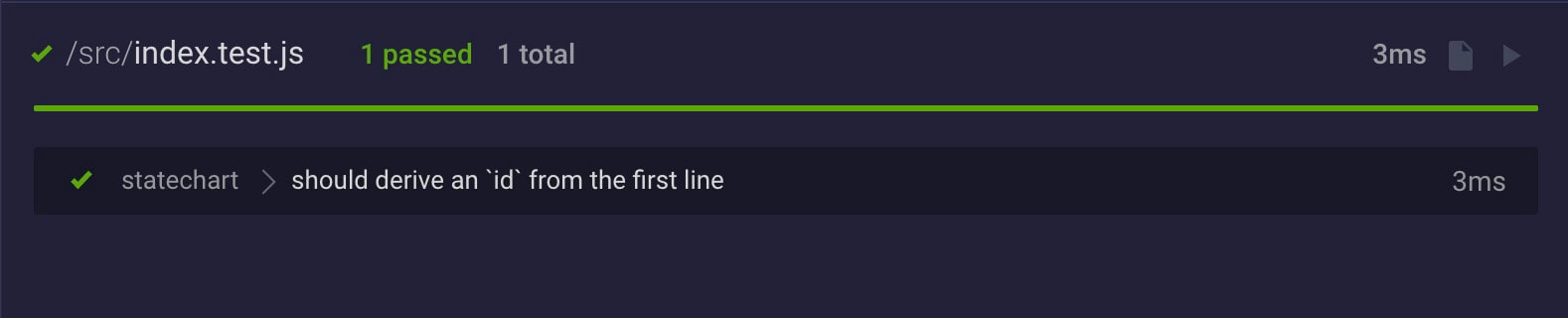

}Next, we should maybe write a couple tests to validate what we’re accomplishing. Let’s start with deriving the id.

describe('statechart', () => {

it('should derive an `id` from the first line', () => {

const chart = statechart(`

lightBulb

`)

expect(chart.id).toEqual('lightBulb')

})

})This, of course, fails because we haven’t made any changes to the code to accomplish this. Let’s write the simplest thing we can to get the test passing.

function statechart(string) {

const id = string.trim()

return {

id,

}

}

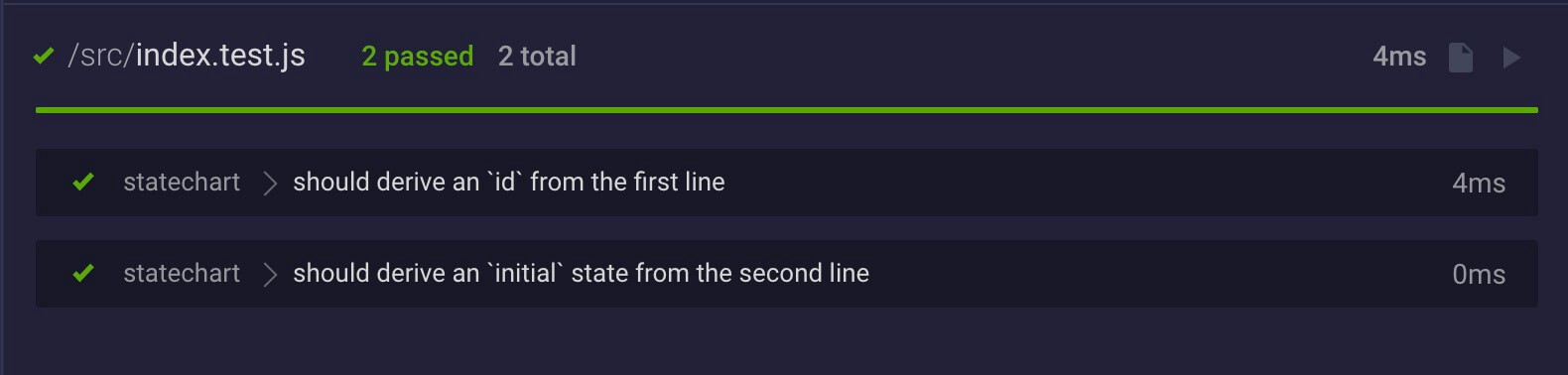

That passes. Now we can add a second test for the initial state.

describe('statechart', () => {

// ...

it('should derive an `initial` state from the second line', () => {

const chart = statechart(`

lightBulb

unlit

`)

expect(chart.initial).toEqual('unlit')

})

})In order to get this test passing, we need to do something a bit more interesting. We need to split our string on new lines in order to separate the two items: id and initial state. We also need to trim those lines and get rid of the whitespace. Lastly, we want to filter out any empty strings.

function statechart(string) {

const parsedString = string

.split(/\n/)

.map(s => s.trim())

.filter(Boolean)

const [id, initial] = parsedString

return {

id,

initial,

}

}

That passes, too. Now let’s go for it and add a test for handling our states.

describe('statechart', () => {

//...

it('should derive the `states` from the rest of the lines', () => {

const chart = statechart(`

lightBulb

unlit

lit unlit TOGGLE

unlit lit TOGGLE

lit broken BREAK

unlit break BREAK

`)

expect(chart.states).toEqual({

lit: {

on: {

TOGGLE: 'unlit',

BREAK: 'broken',

},

},

unlit: {

on: {

TOGGLE: 'lit',

BREAK: 'broken',

},

},

broken: {},

})

})

})This is where the crux of the work takes place. We’ll start by collecting all the rest of the string into an array of stateStrings.

const [id, initial, ...stateStrings] = parsedStringFrom here, we need to turn these into stateNodes. We’re going to turn these into an array of objects with a start, end and event property. It’ll make things easier down the road.

const stateNodes = stateStrings

.map(s => s.split(' '))

.map(([start, end, event]) => ({

start,

end,

event,

}))Now we have a map of these nodes, we need to reduce that down to a single states object.

function statechart(string) {

// ...

const states = stateNodes.reduce((acc, cur) => {

const { start, end, event } = cur

// check if this starting node is in `acc` yet

if (!acc[start]) {

acc[start] = {

on: {},

}

}

// check if the `end` is a state yet

if (!acc[end]) {

acc[end] = {}

}

// Add the event and transition here, spread any previous

// [event]: end key/value pairs

acc[start].on = {

...acc[start].on,

[event]: end,

}

return acc

}, {})

return {

id,

initial,

states,

}

}

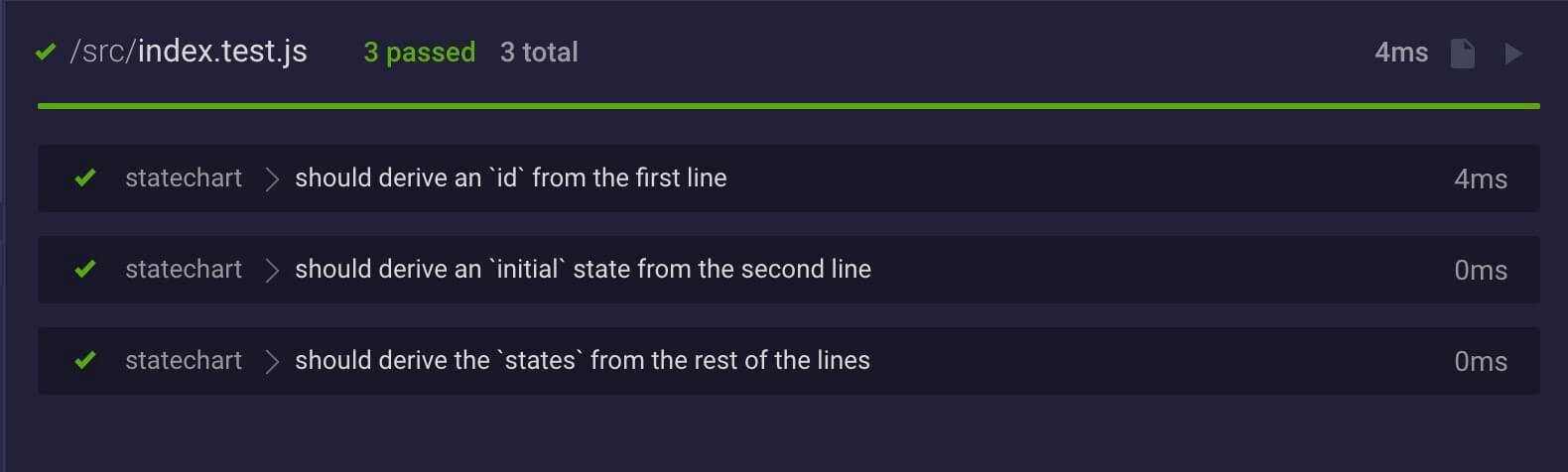

Sweet, this gets our tests all passing! Now we can try it out in a component.

import React from 'react'

import { Machine } from 'xstate'

import { useMachine } from '@xstate/react'

import statechart from './statechart'

const chart = statechart(`

lightBulb

unlit

lit unlit TOGGLE

unlit lit TOGGLE

lit broken BREAK

unlit broken BREAK

lit unlit RESET

broken unlit RESET

`)

const lightBulbMachine = Machine(chart)

function LightBulb() {

const [state, send] = useMachine(lightBulbMachine)

return (

<div>

State: {state}

<div>

<Button onClick={() => send('TOGGLE')}>Toggle</Button>

<Button onClick={() => send('BREAK')}>Break</Button>

<Button onClick={() => send('RESET')}>Reset</Button>

</div>

</div>

)

}And let’s check it out here:

If you want to see this code and play around with it, you can check out this Codesandbox: https://codesandbox.io/s/fsm-as-a-string-g3rcp

Drawbacks to This Approach

I hope it’s clear that this is simply an experiment. I don’t see this as a long-term useful solution. That said, I want to admit the many drawbacks that would happen from adopting this.

- No type safety with TypeScript or Flow

- No

guards for conditional logic - No hierarchical or parallel states

- No

actionsfor side effects - No ability to add top-level

events

Conclusion

I think this approach would really only be useful to someone who wanted to save a few keystrokes in building their machines. I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone!

But, I do recommend experimenting and seeing what you learn. My first iterations on this function involved using tagged templates and I learned a few things about writing those. It never hurts to spend some time trying something in a different way, and I hope this inspires you to try a few more experiments yourself.