Managing Cyclomatic Complexity

I’m not sure when I first learned about “cyclomatic complexity”. It’s such an academic term that you can practically smell a classroom or library when you read or hear it. If I had understood the concept earlier in my career, I don’t think I would have given it much thought.

”I’ve got buttons to put on these web pages. Who cares about cycles? What the heck is a cycle anyways?!” a younger, more naive Kyle may have exclaimed.

I don’t think that way anymore. In fact, I have been thinking about cyclomatic complexity almost daily for a little over six months. Over this time, I’ve developed some thoughts and ideas on the topic that I want to share with you in this post. By the end, I hope I will have convinced you of the importance of cyclomatic complexity in writing maintainable applications.

To get started, I have a simple question for you. How many logical paths are there through the following function? I assure you, it’s not a trick question.

function double(num) {

return num * 2

}I hope you came up with the answer one. There is only one logical path through the function. We give it an input, we get an output.

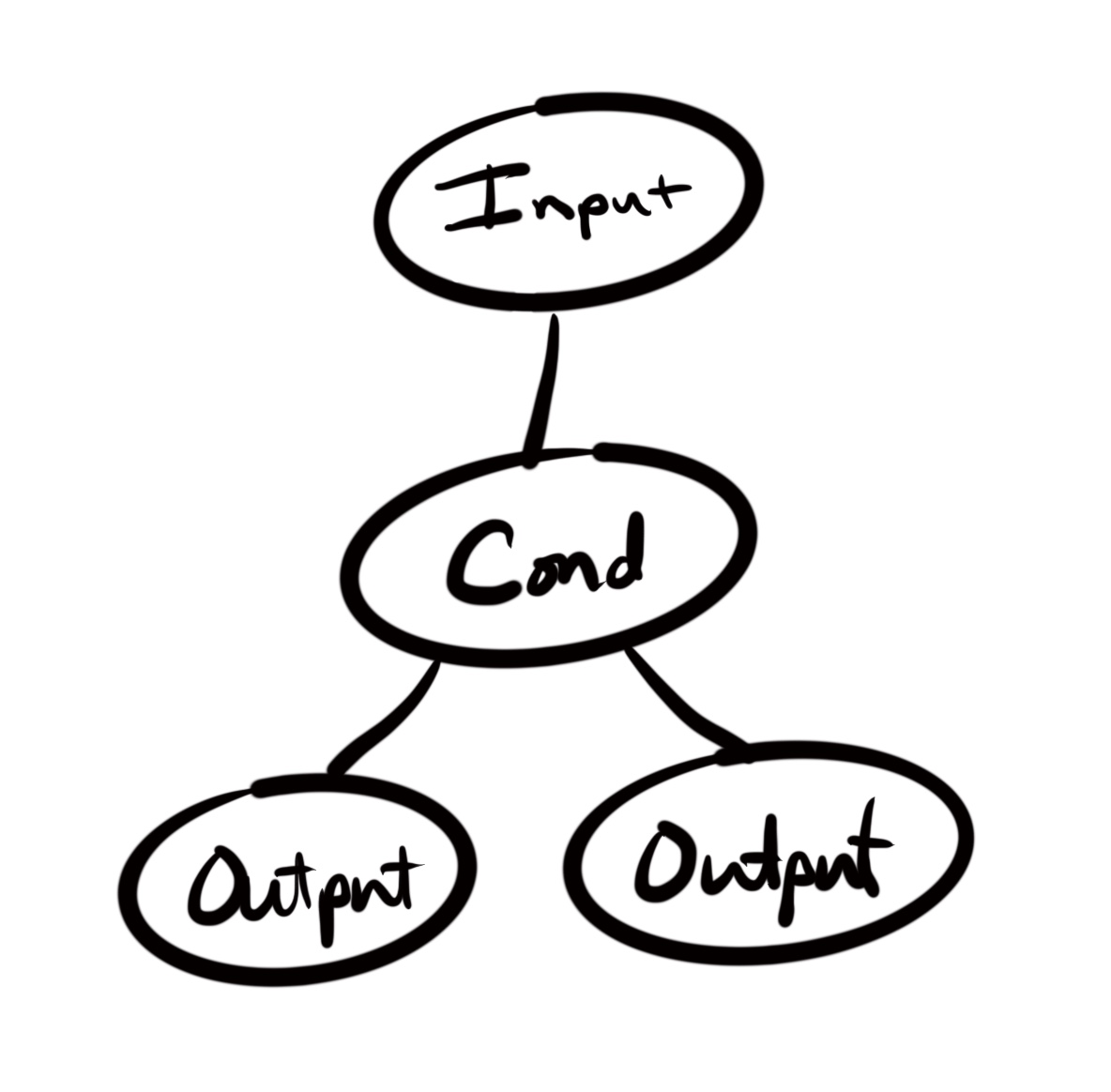

What if we add a conditional inside of the function? Let’s use a well known function in mathematics for this example. How many logical paths are there in this function?

function collatz(num) {

if (num % 2 === 0) {

return num / 2

}

return 3 * num + 1

}Again, not a trick question, the answer is two. There are two paths through this function. Either a number is an even number and we return the first branch, or a number is odd and we return the second branch.

Another way to describe this function is that it takes 2 cycles through it to touch every logical branch of the program. These cycles are how we get the term “cyclomatic”. The more cycles, the greater the complexity.

Let’s take a look at a far more complex example. This is known as the “Gilded Rose” kata . You can Google it and find solutions to it all over . I was once given a take home exercise that was basically this kata adjusted for items the company worked with. It looks like this:

class Item {

constructor(name, sellIn, quality) {

this.name = name

this.sellIn = sellIn

this.quality = quality

}

}

class GildedRose {

constructor() {

this.items = []

}

addItem(item) {

this.items.push(item)

}

updateQuality() {

const { items } = this

for (var i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

if (

'Aged Brie' != items[i].name &&

'Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert' != items[i].name

) {

if (items[i].quality > 0) {

if ('Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros' != items[i].name) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality - 1

}

}

} else {

if (items[i].quality < 50) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality + 1

if ('Aged Brie' == items[i].name) {

if (items[i].sellIn < 6) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality + 1

}

}

if ('Aged Brie' == items[i].name) {

if (items[i].sellIn < 11) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality + 1

}

}

if ('Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert' == items[i].name) {

if (items[i].sellIn < 11) {

if (items[i].quality < 50) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality + 1

}

}

if (items[i].sellIn < 6) {

if (items[i].quality < 50) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality + 1

}

}

}

}

}

if ('Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros' != items[i].name) {

items[i].sellIn = items[i].sellIn - 1

}

if (items[i].sellIn < 0) {

if ('Aged Brie' != items[i].name) {

if ('Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert' != items[i].name) {

if (items[i].quality > 0) {

if ('Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros' != items[i].name) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality - 1

}

}

} else {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality - items[i].quality

}

} else {

if (items[i].quality < 50) {

items[i].quality = items[i].quality + 1

}

if ('Aged Brie' == items[i].name && items[i].sellIn <= 0)

items[i].quality = 0

}

}

if ('Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros' != items[i].name)

if (items[i].quality > 50) items[i].quality = 50

}

return items

}

}

const rose = new GildedRose()

rose.addItem(new Item('+5 Dexterity Vest', 10, 20))

rose.addItem(new Item('Aged Brie', 2, 0))

rose.addItem(new Item('Elixir of the Mongoose', 5, 7))

rose.addItem(new Item('Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros', 0, 80))

rose.addItem(new Item('Backstage passes to a TAFKAL80ETC concert', 15, 20))

rose.addItem(new Item('Conjured Mana Cake', 3, 6))

rose.updateQuality()Want to hazard a guess how many cycles the updateQuality method has?

I’ll wait.

Got it yet?

It’s 25! It takes 25 cycles to cover every branch of this function.

For the record, it wasn’t my amazing brain that could read that code and know the answer was 25. I used JSHint in the browser to check it out. Another good option would be to use the complexity rule from ESLint.

I hope it just dawned on you that this also means you have to write 25 tests to have confident coverage regarding updateQuality. A method this complex demands good tests.

Now, I don’t plan to solve this problem for you in the rest of this post. In fact, I recommend watching this video from Sandi Metz that covers the subject. Rather, I want to explore how I think about handling complexity in situations like these.

How Complexity Exists in A Program

Before we learn how to deal with complexity, we must first learn some truths about complexity. I’m going to work through a bit of a metaphor here. I’m not sure it will land with everyone, but I hope it helps some of you understand “complexity” in a new way.

First, I want to be clear, that I am not describing subjective complexity. This is not about what programming style you prefer, or your preference for for loops instead of forEach. This is about an objective measurement of complexity in an application.

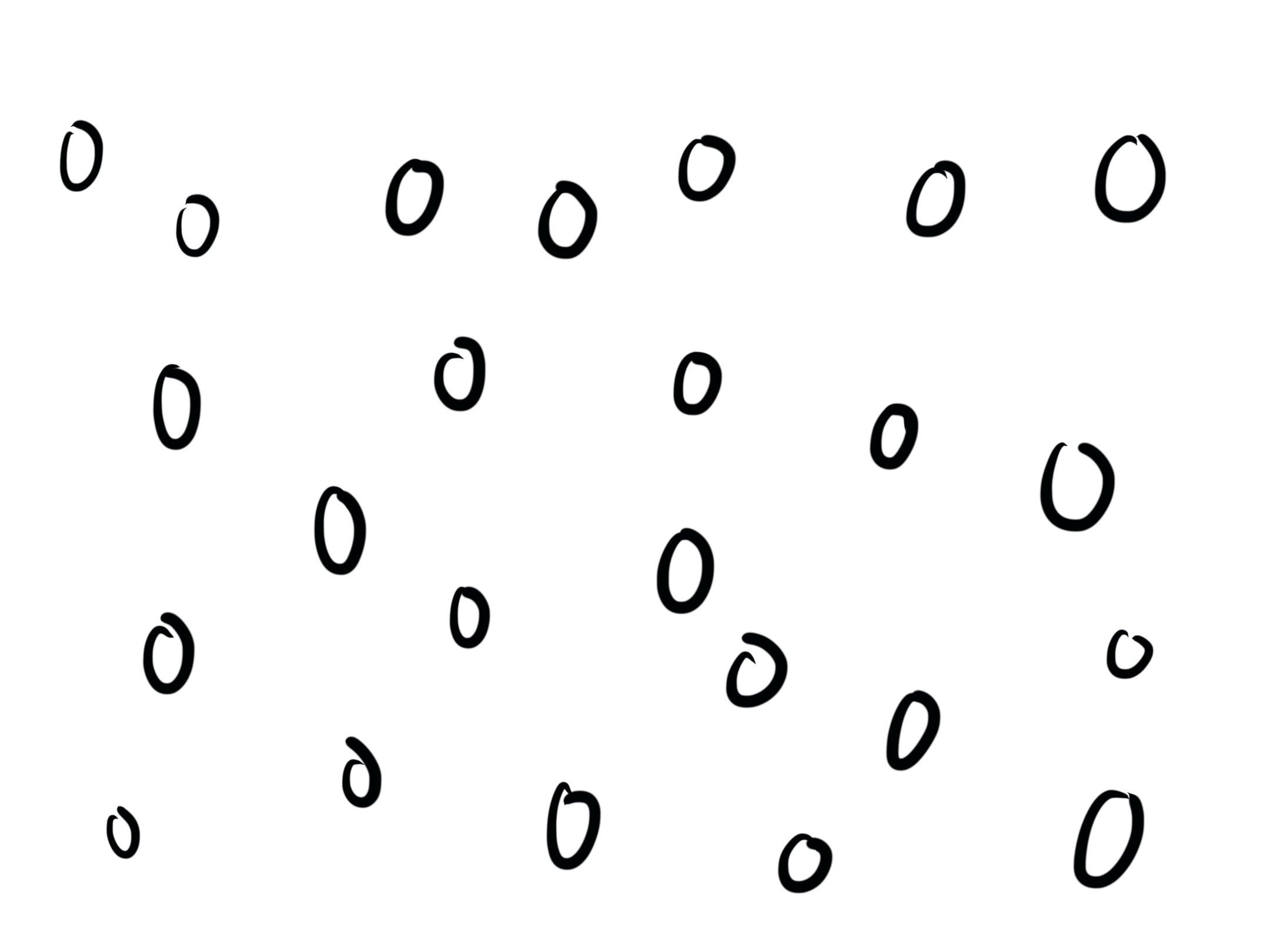

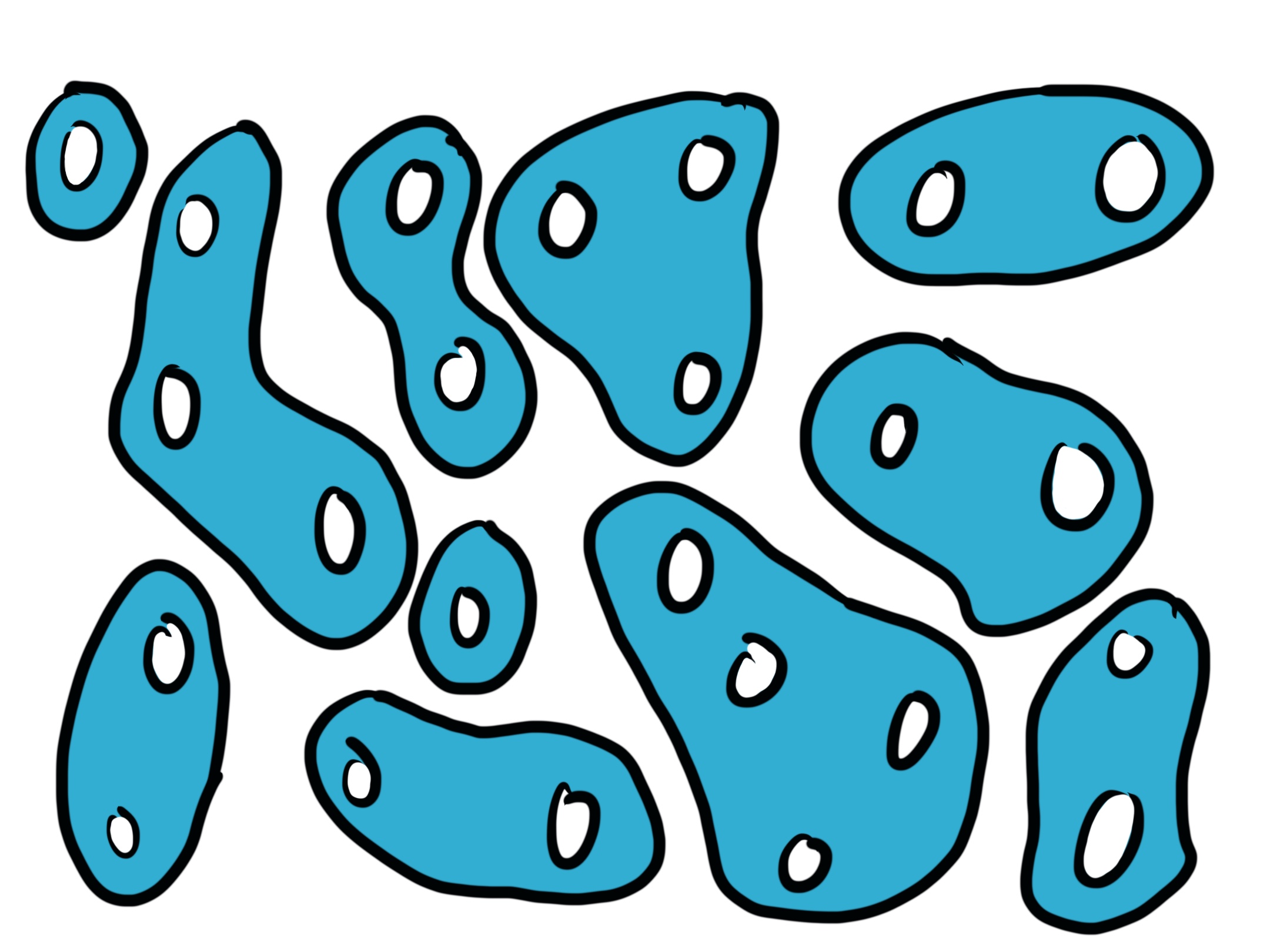

Every program has a minimum level of overall complexity that is required to exist. That is, without removing features from the program, it will have an aggregate complexity score of X, where X represents the minimum complexity required to accomplish that program. Let’s imagine a program, as a collection of nodes.

Now, we cannot reduce X without changing the observable behavior of the program. If our program has even X - 1 nodes, it will not be the same program anymore. However, we are allowed to group the nodes of X (these would typically be functions, classes, modules, etc.). How we group them matters.

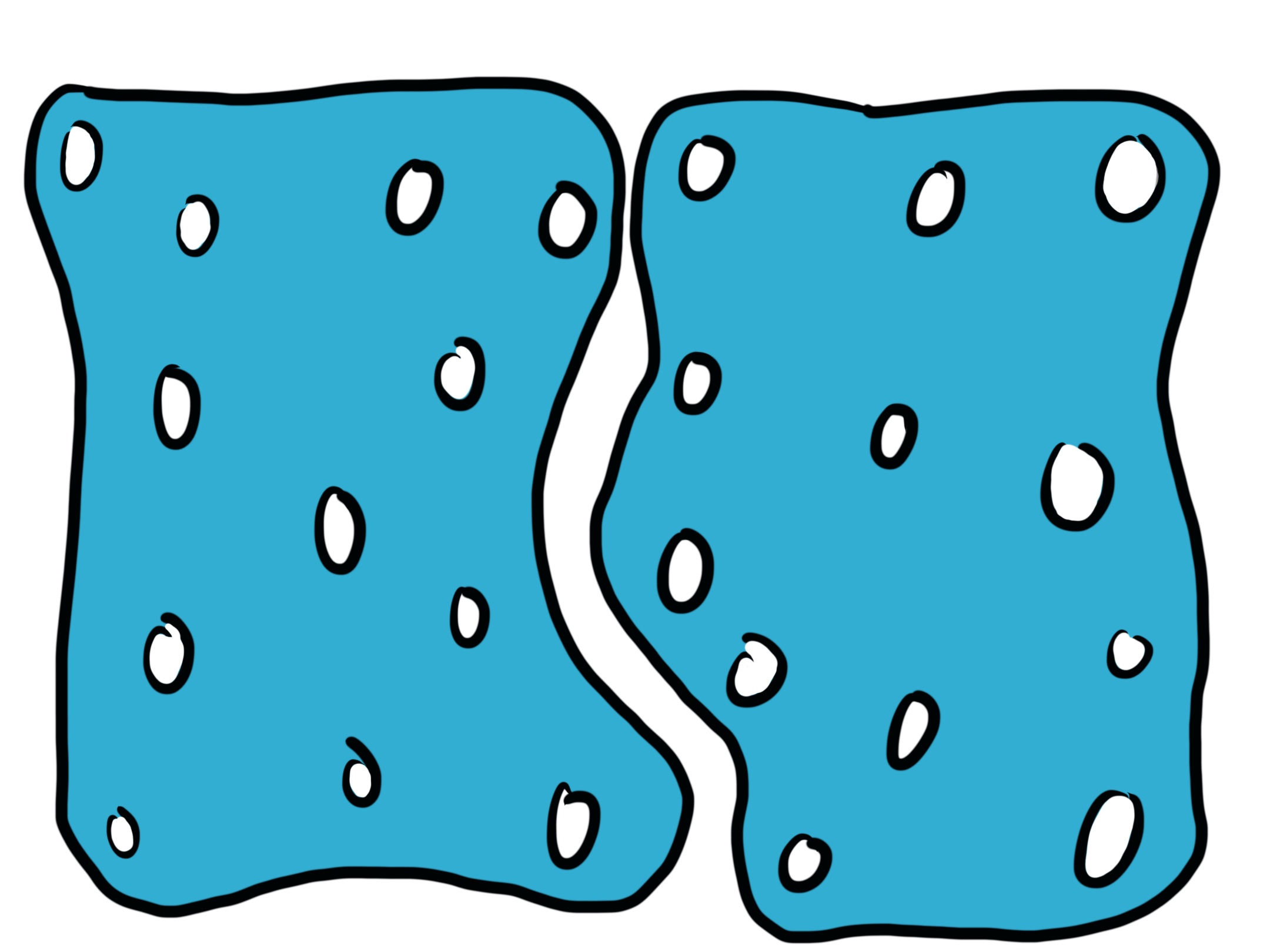

We might group them in two big groups where the average complexity of our groups is very high.

We also might group our nodes in many small groups, where the average complexity of those groups is very low.

Regardless of how we group the nodes of our program, the overall number of nodes, and therefore the overall complexity of the system, remains as the value X. What does change is the average complexity per group. Understanding this is the starting point to managing complexity more purposefully in our programs.

In General, Aim for Low Complexity Per Group

The first thing we can recognize when managing complexity is that, in general, code with low complexity is easier to understand than code with high complexity. The first few examples I shared, the double and collatz functions are quite easy to understand. The Gilded Rose, however, is an almost impenetrable bit of code. I imagine some of the functions in your codebases look even worse (admit it).

Functions with a low score are not only easy to understand, but are easier to test. Sometimes, they are so easy to understand you may not bother with a test at all (not that I advocate for that, but I understand the impulse). These low complexity scores also mean that whenever we need to make an adjustment to one of the groups, it is relatively easy to do so. Update a test, make some changes, and you’re good to go. This gives us a lot of confidence in our programs.

But I say “in general” on purpose. There are a few scenarios where it may make sense to allow a high level of complexity to exist in a particular group.

The Exception: Encapsulated Complexity

Since we cannot change the overall complexity of a program, we need to be aware of how we manage complexity in “groups” of our program. There will come times where it may make sense to allow a particular “group” a high level of complexity.

So what makes a good candidate for making an exception?

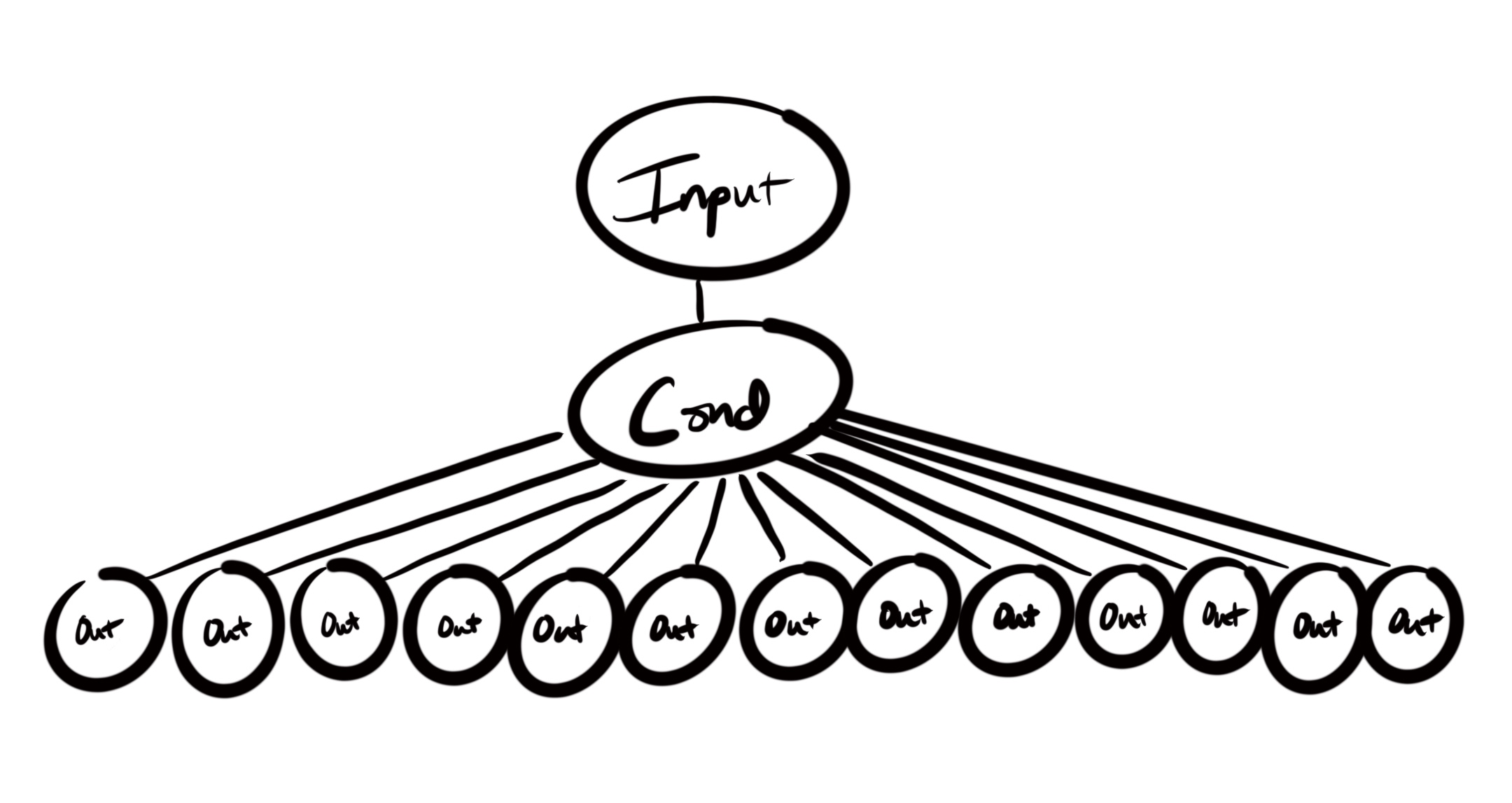

I think the most common reason to allow a part of a program to have a high level of complexity is when there is a single conditional that has many results. Most often, this is a switch case or something similar. The structure of that part of the program might look like this:

The reason this makes sense is that the condition and mapping to appropriate results has to happen somewhere in our program. It might as well be in an isolated and encapsulated place. That place should often be a well named (and tested) function that only handles a single part of our program.

The encapsulation of the complexity is key here. Remember, we cannot change X (the overall complexity) and have the same program. We know we must have this complexity somewhere, but by grouping it like this, we reduce exposure of the internal complexity to rest of our program. We essentially make a contract with ourselves and anyone who may work on this code in the future, “We have contained the complexity, do not let it leak out.”

The most common example I can think of in modern web development would be a state reducer, a la Redux or the useReducer hook. For those who are not sure what a state reducer is, a state reducer is a function that accepts a state and an action argument and returns the nextState. The actions passed to this reducer might be of many different types, and each must be accounted for. This results in a function that has a single condition (what type of action is this?), but many possible results. Breaking this apart might only make the program more difficult to use or reason about. Capturing it in a single function makes the most sense, even if the complexity score might be very high.

An Example From My Work

A few months ago, I came across a bit of code that had a high level of complexity for a single group. I’m going to share the change I made, and hopefully you’ll agree that it was the right way to manage the complexity.

The code that follows is adapted from the Webflow codebase. Webflow’s architecture involves a lot of “nodes” and these nodes contain various types of information that need to be validated, cleaned up, and transformed. At one particular point during those transformations, I found code that looks somewhat like this:

// This code uses ImmutableJS Maps, not standard JS Maps

// hence the method `update()` and more.

nodes.update('dynamicData', Immutable.Map(), dynamicData => {

const bindableData = dynamicData

.get('bindable', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpBindings(bindingDep1, bindingDep2))

if (bindableData.size > 0) {

dynamicData = dynamicData.set('bindable', bindableData)

} else {

const originalBindings = dynamicData.get('bindable')

dynamicData =

originalBindings && originalBindings.size === 0

? dynamicData

: dynamicData.delete('bindable')

}

const conditionalData = dynamicData

.get('conditions', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpConditions(conditionalDep1, conditionalDep2))

dynamicData =

conditionalData.size > 0

? dynamicData.set('conditions', conditionalData)

: dynamicData.delete('conditions')

const filterableData = dynamicData

.get('filterable', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpFilters(filterDep1, filterDep2))

if (filterableData.size > 0) {

dynamicData = dynamicData.set('filterable', filterableData)

} else {

const originalFilter = dynamicData.get('filterable')

dynamicData =

originalFilter && originalFilter.size === 0

? dynamicData

: dynamicData.delete('filterable')

}

const sortableData = List()

.concat(dynamicData.get('sortable', List()))

.update(cleanUpSort(sortableDep1, sortableDep2))

if (sortableData.size > 0) {

dynamicData = dynamicData.set('sortable', sortableData)

} else {

dynamicData = dynamicData.delete('sortable')

}

return dynamicData

})There’s a lot going on in this function, and I don’t expect it to make a ton of sense right away. Let me try and break it down a little bit. This function receives a piece of data, dynamicData, and mutates it as necessary based on which conditionals are met along the way. That’s pretty standard for programming.

The complexity score isn’t terribly high, it’s only a 7, but the code is still more difficult to reason about than necessary and has too many responsibilities. We can make this better. With some changes, this bit of code will be easier to understand and update in the future, while also reducing the average complexity per group.

First, we need to identify what the groups are in this code. It turns out there are four distinct groups in this bit of code: one that updates the bindings, one that updates the conditions, one that updates the filters, and finally one that updates the sorts. Here they are as separate code blocks:

// Bindings

const bindableData = dynamicData

.get('bindable', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpBindings(bindingDep1, bindingDep2))

if (bindableData.size > 0) {

dynamicData = dynamicData.set('bindable', bindableData)

} else {

const originalBindings = dynamicData.get('bindable')

dynamicData =

originalBindings && originalBindings.size === 0

? dynamicData

: dynamicData.delete('bindable')

}// Conditions

const conditionalData = dynamicData

.get('conditions', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpConditions(conditionalDep1, conditionalDep2))

dynamicData =

conditionalData.size > 0

? dynamicData.set('conditions', conditionalData)

: dynamicData.delete('conditions')// Filters

const filterableData = dynamicData

.get('filterable', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpFilters(filterableDep1, filterableDep2))

if (filterableData.size > 0) {

dynamicData = dynamicData.set('filterable', filterableData)

} else {

const originalFilter = dynamicData.get('filterable')

dynamicData =

originalFilter && originalFilter.size === 0

? dynamicData

: dynamicData.delete('filterable')

}// Sorts

const sortableData = List()

.concat(dynamicData.get('sortable', Immutable.List()))

.update(cleanUpSort(sortableDep1, sortableDep2))

if (sortableData.size > 0) {

dynamicData = dynamicData.set('sortable', sortableData)

} else {

dynamicData = dynamicData.delete('sortable')

}If we pay attention, we can see that each of these groups takes dynamicData and conditionally updates it. We can turn each of these groups into their own function that receives dynamicData as an argument, and returns the transformed data. We need to gather all the other data necessary for each function, but that isn’t too hard. Those functions look like this:

const updateBindings =

({ bindingDep1, bindingDep2 }) =>

dynamicData => {

const bindableData = dynamicData

.get('bindable', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpBindings(bindingDep1, bindingDep2))

if (bindableData.size > 0) {

return dynamicData.set('bindable', bindableData)

} else {

const originalData = dynamicData.get('bindable')

return originalData && originalData.size === 0

? dynamicData

: dynamicData.delete('bindable')

}

}

const updateConditions =

({ conditionalDep1, conditionalDep2 }) =>

dynamicData => {

const conditionalData = dynamicData

.get('conditions', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpConditions(conditionalDep1, conditionalDep2))

return conditionalData.size > 0

? dynamicData.set('conditions', conditionalData)

: dynamicData.delete('conditions')

}

const updateFilters =

({ filterableDep1, filterableDep2 }) =>

dynamicData => {

const filterableData = dynamicData

.get('filterable', Immutable.Map())

.update(cleanUpFilters(filterableDep1, filterableDep2))

if (filterableData.length) {

return dynamicData.set('filterable', filterableData)

} else {

const originalData = dynamicData.get('filterable')

return originalData && originalData.size === 0

? dynamicData

: dynamicData.delete('filterable')

}

}

const updateSorts =

({ sortableDep1, sortableDep2 }) =>

dynamicData => {

const sortableData = dynamicData

.get('sortable')

.update(cleanUpSort(sortableDep1, sortableDep2))

return sortableData.size > 0

? dynamicData.set('sortable', sortableData)

: dynamicData.delete('sortable')

}Now each function is an isolated bit of complexity. You might be wondering why each of these functions is a curried function (You can learn more about curried functions here). Currying these functions allows me to do two things.

First, it allows me to supply all the extra arguments necessary to do the computation ahead of time. These are held in closure for the next function accepting dynamicData as an argument.

Second, it allows me to create a composition of these functions. Because the returned function from each updater here has the same signature (and returns the same signature), I can compose them together. I’ve written about composition here and I encourage you to read that post. I will actually use the pipe function for this example, so that we maintain left-to-right, top-to-bottom data flow through our composition. Our new update looks like this:

nodes.update('dynamicData', Immutable.Map(), dynamicData => {

// These aren't the real arguments, just useful for the examples

return pipe(

updateBindings({

bindingDep1,

bindingDep2,

}),

updateConditions({

conditionalDep1,

conditionalDep2,

}),

updateFilters({

filterableDep1,

filterableDep2,

}),

updateSorts({

sortableDep1,

sortableDep2,

}),

)(dynamicData)

})How much simpler is that bit of code? It even reads more like English because of how we’ve named our functions. I need to make an update to the data. It will be piped through these four functions, each of which has a fairly low level of complexity, and return the result.

We have not changed the overall complexity. It remained constant as it must, but we have changed the average complexity per function to 1.5. That is significantly lower than a complexity score of 7. I’m biased because I wrote the code, but I think this is objectively better to work with as well. What do you think?

Takeaway

Paying attention to cyclomatic complexity can be a game changer in your programming career. It can take you from being the kind of person that writes code that works (which is awesome), to writing code that is easier for you and others to make changes to (which is awesomer). Recognizing complexity and developing strategies for managing it are important for creating maintainable and reasonable programs.

Remember, we can’t change the overall complexity of a program without changing what the program is. Try to keep average complexity per group low. Many functions, classes, modules with low complexity is often (but not always) easier to manage. Encapsulate high levels of complexity where necessary as an exception.